Why is Microbial Access to SOM Important?

Microbial access to organic matter is a significant control on carbon cycling in soils. How do we reconcile the enormous capability of microbes to decompose organic matter with the enormous amount of C that is stored in soil (Eckschmitt et al. 2005)? If SOM is accessible to microbes, they will degrade it, regardless of its chemical structure (Dungait et al, 2012). However, if it is not accessible, that SOM can remain in the soil for very long time periods. At the long timescales relevant to global carbon cycle models (i.e., decades to millennia), the strongest influences aren’t the processes that occur in seasonal or even annual cycles (e.g. plant growth or litter production). Rather, the strongest influence is the production of stabilized materials in mineral soil - the “big, slow pools”.

Physical Protection of SOM

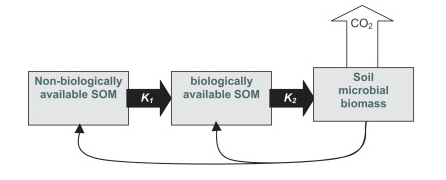

Physical protection of SOM has been recognized for decades as a key control over its fate and dynamics. More recently, Kemmitt et al (2008) synthesized this research on the importance of microbial accessibility in the dynamics of SOM mineralization and termed it “The Regulatory Gate Hypothesis”. According to the Regulatory Gate Hypothesis (Figure 1), the rate-limiting step of SOM mineralization is an abiotic one, later explained as a breakdown of physical and/or energetic barriers, but essentially referring to the accessibility of SOM to soil microbes.

Figure 1, from Kemmitt et al (2008). DOI: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.06.021

Figure 1, from Kemmitt et al (2008). DOI: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.06.021

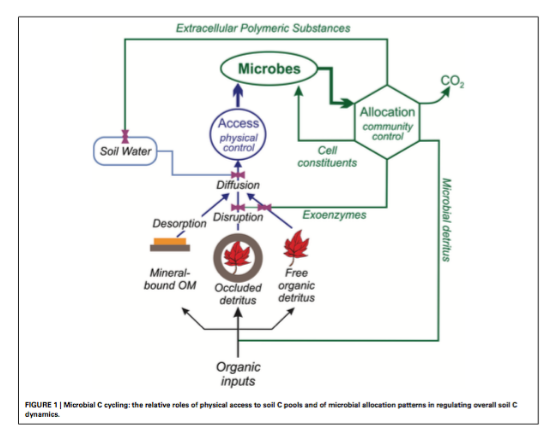

As described by Schimel and Schaeffer (2012) and shown in Figure 2, the rate at which OM in soil can be metabolized is limited by microbes’ ability to access it (“access”). The fate of that OM once it is accessed depends on how soil microbial communities allocate that C to cellular and extracellular metabolic activities. Figure 2 shows the roles of both physical access to and allocation of soil carbon in the overall dynamics of soil carbon.

Figure 2, from Schimel and Schaeffer (2012). DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00348

Figure 2, from Schimel and Schaeffer (2012). DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00348

Limits on Microbial Access to SOM

What influences microbial access to SOM? Water, oxygen, substrate, and organism must all come together (in space and time) for SOM turnover at the pore-space level (Kuka et al, 2007). The physical protection of SOM from microbial decomposition has a few major drivers: occlusion within aggregates, adsorption onto minerals, the spatial heterogeneity within soils, and wet/dry cycles that may promote or inhibit diffusion.

Important Publications:

Dungait et al, 2012 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02665.x

Ekschmitt et al, 2005 DOI: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.024

Schimel and Schaeffer, 2012 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00348

1. Occlusion

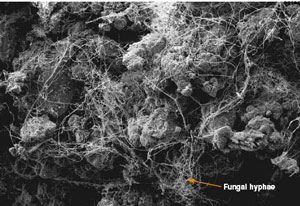

Figure 3, showing a soil microaggreg1ate from https://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/soils/soil-properties/the-soil-is-alive/

Figure 3, showing a soil microaggreg1ate from https://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/soils/soil-properties/the-soil-is-alive/

Occlusion within water-stable soil aggregates and soil nano-sized pores are important processes that can render SOM inaccessible to microbes. One way that aggregates contribute to inaccessibility is by limiting movement of microbial enzymes. Aggregates can also limit access to other resources such as oxygen, thereby reducing microbial activity. In order to make aggregate-bound SOM available for microbial decomposition, both physical disruption and exoenzymes are often necessary. Microaggregates (53 – 250 um in diameter) tend to store C longer than macroaggregates (> 250 um), perhaps because of less disturbance and more occlusion in microaggregates.

2. Adsorption

Figure 4, visualizing adsorption, from https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adsorption

Figure 4, visualizing adsorption, from https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adsorption

Adsorption onto minerals is another way that SOM can be physically protected from microbial consumption. SOM is adsorbed onto the surfaces of clay particles and amorphous iron and aluminum colloids because of the large charged surface area covered by these charged molecules. This can protect SOM from microbial decomposition because adsorption prevents microbes from taking up the molecule and even blocks exoenzymes from being able to react with them.

3. Spatial Heterogeneity of the Soil

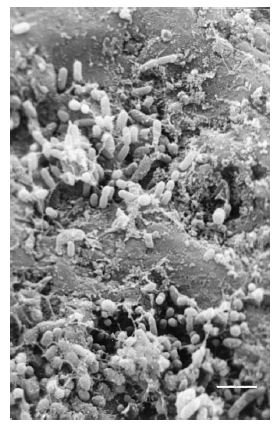

Figure 5 showing the heterogeneous soil landscape, from Or et al. (2007). DOI:10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.05.025

Figure 5 showing the heterogeneous soil landscape, from Or et al. (2007). DOI:10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.05.025

The complex spatial heterogeneity of the physical landscape within soils contributes to the physical protection of SOM against microbial decomposition. The distance and/or difficulty of moving through soils can inhibit microbial access to SOM. This can protect organic molecules from attack if the energy it costs for a microbe to reach the SOM is greater than the energy it acquires from decomposing it. Deeper soils tend to protect SOM more than shallow soils simply because there is less connectivity between microbes and substrates (Ekschmitt et al, 2008).

4. Wet/Dry Cycles

Figure 6, wet and dry soils, from https://www.shutterstock.com/video/search/wet-soil and https://www.featurepics.com/online/Dry-Soil-Background-Photo396566.aspx

Figure 6, wet and dry soils, from https://www.shutterstock.com/video/search/wet-soil and https://www.featurepics.com/online/Dry-Soil-Background-Photo396566.aspx

Lastly, wet/dry cycles in soils affect the availability of SOM to microbes. Microbes depend on water in soil for many reasons. First, dry soils can effectively immobilize bacteria that depend on water films to allow them or their enzymes to move through soils. Second, a lack of water can prevent diffusion which is a major pathway for materials transferred both into and out of microbial cells. Lastly, water helps solubilize resources and render them more accessible to microbes and without it, many molecules remain sorbed to mineral surfaces.

Applications to Earth Systems Models (ESMs)

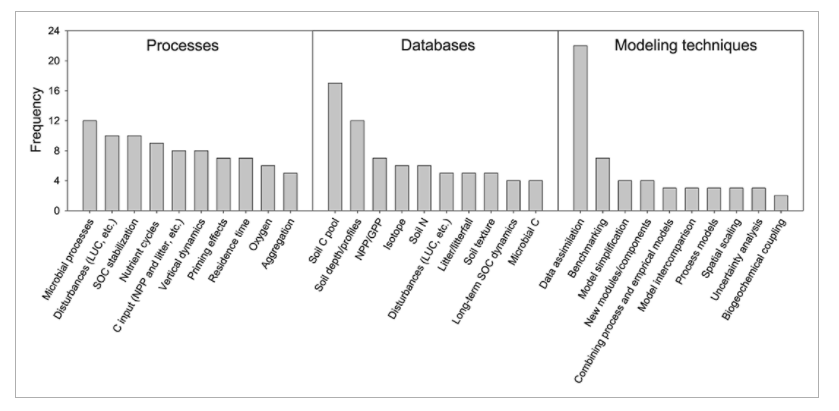

Currently, researchers are trying to more accurately portray soil carbon dynamics in Earth System Models (ESMs). In a recent review paper, Luo et al (2016) acknowledged some of the shortcomings of current models for soil carbon dynamics, a major one being how models treat microbial influences on soil C. Figure 3 shows a consensus on recommended soil processes, databases, and modeling techniques to direct future work in ESMs. Microbial processes and SOC stabilization fall in the top 3 of the priorities to improve ESMs. ESM’s also need better data sets on soil C pools to be able to test and validate the models. By continuing to focus on microbial access to SOM, and even by increasing our emphasis on this process, we should be able improve the accuracy of ESM models.

Figure 7, from Luo et al. (2016). DOI: 10.1002/2015GB005239

Figure 7, from Luo et al. (2016). DOI: 10.1002/2015GB005239

Current ESMs use simple equations and matrices to describe soil carbon dynamics, yet they disagree widely in their projections. Wieder et al (2015) are working to explicitly include non-linear microbial dynamics into their models to explain microbial stabilization and destabilization of soil C. Microbial accessibility to substrates has not been parameterized in ESMs but may be key in determining the magnitude of microbial effects on SOM turnover (Wieder et al, 2015, Schimel and Shaeffer, 2012). However, Luo et al (2016) suggest the need for further observation and evaluation before these can be effectively incorporated into ESMs.

Important Publications:

Wieder et al, 2015 DOI: 10.1002/2015GB005188

Luo et al, 2016, DOI: 10.1002/2015GB005239

References

Dungait, J., Hopkins, D., Gregory, A., Whitmore, A. (2012) Soil organic matter turnover is governed by accessibility not recalcitrance. Global Chnage Biology, 18, 1781-1796. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02665.x

Ekschmitt K, Liu M, Vetter S, Fox O, Wolters V (2005) Strategies used by soil biota to overcome soil organic matter stability – why is dead organic matter left over in the soil? Geoderma, 128, 167–176.

Ekschmitt K, Kandeler E, Poll C et al. (2008) Soil carbon preservation through habitat constraints and biological limitations on decomposer activity. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 171, 27–35.

Kemmitt SJ, Lanyon CV, Waite IS et al. (2008) Mineralization of native soil organic matter is not regulated by the size, activity or composition of the soil microbial biomass – a new perspective. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 40, 61–73. DOI: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.06.021.

Kuka K, Franko U, Ru ̈hlmann J (2007) Modelling the impact of pore space distribution on C turnover. Ecological Modelling, 208, 295–306.

Luo, Y. Q. et al. (2016) Toward more realistic projections of soil carbon dynamics by Earth system models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 40–56, DOI: 10.1002/2015gb005239.

Or, D. et al. (2007) Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media - a review. Advances in Water Resources 30, 1505-1527, DOI: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.05.025.

Schimel, J., and S. Schaeffer (2012) Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Frontiers in Microbiology 3, 1-11, DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00348.

Six J, Elliott E, Paustian K (2000) Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: a mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol- ogy and Biochemistry, 32, 2099–2103.

Six J, Conant R, Paul E, Paustian K (2002) Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil, 241, 155– 176.

Wieder, W. R., et al., (2015) Explicitly representing soil microbial processes in Earth system models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 29, DOI: 10.1002/2015GB005188.